Why LLMs Aren't Enough – and Why Agents Are Inevitable

I. Introduction: AI is Everywhere – but Not All AI is the Same

Over the past few years, artificial intelligence has quietly gone from a research topic to something you bump into every day. It writes parts of our emails, suggests what we should watch next, edits photos, summarizes documents, answers questions, and occasionally argues with us too.

AI shows up in ads, search bars, customer support chats, productivity tools, and sometimes in places you don't even notice anymore. There's no doubt that it has reshaped our sense of what software can do; tasks that used to take hours now take minutes; things that felt impossible a decade ago are suddenly normal.

But with this rapid rise came a flood of new terms.

Machine Learning.

Deep Learning.

Neural Networks.

Generative AI.

Prompts.

Large Language Models.

Agents.

These words are often used interchangeably – sometimes incorrectly – and often without much explanation. That confusion matters – because not all AI works the same way, and not all AI is suited for the same kinds of problems.

In this post, we'll focus on two of the most commonly mixed-up concepts today: Large Language Models (LLMs) and Agents. Not from a textbook point of view, but from how they actually behave in the real world – and why that difference is more important than it sounds.

II. The Confusion: LLMs are NOT Agents

Let's start with something familiar.

Imagine opening ChatGPT and asking it to summarize a document. You paste the text, hit enter, and within seconds you get a clean, coherent summary. It feels almost magical. The task is done, and you move on.

Now imagine asking something slightly different.

Instead of "summarize this," you ask:

"Go through my internal files, pull relevant data from last quarter, check recent earnings calls, update my model, and draft slides explaining the changes."

At first glance, this doesn't feel fundamentally different. It's still AI, right? But in practice, this is where things start to break down. You might get a partial response, or a confident explanation that still requires you to manually fetch files, verify numbers, and stitch everything together yourself. The AI helps, but it doesn't finish.

What's happening here isn't a lack of intelligence. It's a mismatch between the task and the system you're using.

Most people assume that because both experiences involve AI, they're powered by the same thing doing the same job at different levels of sophistication. They're not. The difference isn't how smart the AI is – it's how it behaves over time.

This is where the distinction between Large Language Models and agents actually matters.

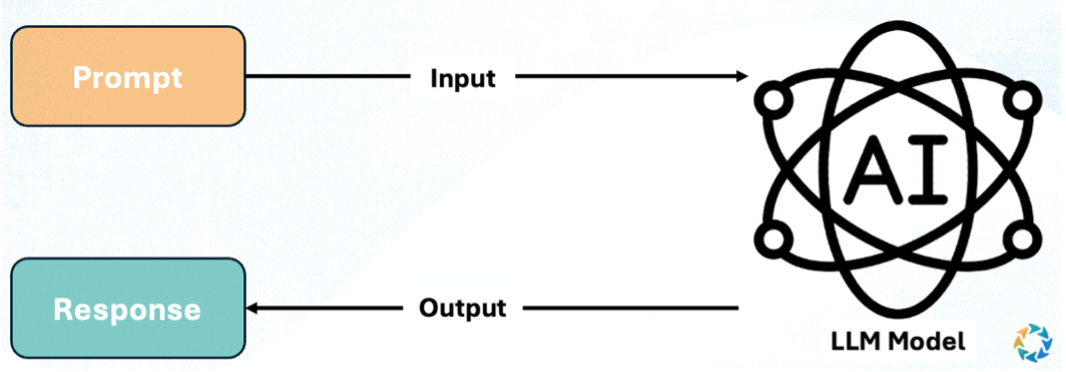

An LLM is exceptionally good at producing a single response; you give it input, it reasons within that moment, and it gives you an output. Once the answer is delivered, the job is done. It doesn't decide what should happen next, it doesn't hold a goal in the background, and it doesn't keep working unless you explicitly ask it to.

An agent, by contrast, behaves much more like a process than a response.

A useful mental model here is J.A.R.V.I.S. from Iron Man.

J.A.R.V.I.S. isn't impressive because he answers Tony Stark's questions. He's impressive because he sticks around. He monitors systems, keeps track of goals, runs checks in the background, pulls information from different sources, and adjusts when circumstances change. Tony doesn't need to re-explain the context every time – J.A.R.V.I.S. already knows what's going on and what needs to happen next.

That's much closer to how agents are designed to behave.

An agent can hold a goal over time, break it into steps, use tools along the way, observe what happens, and decide what to do next. The Large Language Model is still there – it's doing the reasoning, interpretation, and language generation – but it's no longer the entire system. It's one component inside a larger loop.

This is the key insight behind much of today's confusion:

LLMs generate answers.

Agents execute processes.

Once you see that distinction, a lot of modern AI behavior suddenly makes sense. It explains why chat-based tools feel incredible for one-off questions but fragile for real workflows. It explains why many "AI copilots" seem promising in demos but stall halfway through actual work. And it hints at why the next generation of AI software feels less like chatting, and more like delegation.

In the next sections, we'll dig into what LLMs excel at, where they hit their limits, and why agents are emerging as the layer that finally turns AI from something that responds into something that gets things done.

III. What LLMs are and what they are Good At

To understand what Large Language Models are good at, it helps to start with what they actually are – not what they appear to be from the outside.

At their core, LLMs are language models trained using machine learning. Machine learning, broadly speaking, is a way of building systems that don't follow hard-coded rules, but instead learn patterns from data. Rather than telling a computer exactly how language works, we expose it to enormous amounts of text and let it learn the statistical structure of language on its own.

LLMs are trained using a technique called self-supervised learning. That means the model learns without humans explicitly labeling the data. Instead, it repeatedly performs a simple task given part of a sentence, predict what comes next. Over billions– or trillions– of examples, the model becomes extremely good at this prediction game. As it turns out, being very good at predicting the next word requires a broad understanding of grammar, semantics, style, facts, and even a surprising amount of reasoning.

This is the foundation behind systems like OpenAI's ChatGPT, Anthropic's Claude, and Google's Gemini. Despite differences in training, scale, and philosophy, they all share the same fundamental mechanics.

One subtle but important detail is that LLMs don't see words the way humans do. Machine learning models operate on numbers, not text. So before anything else happens, language must be translated into a numerical form through a process called tokenization.

Tokenization breaks text into small units called tokens. These tokens might be whole words, pieces of words, punctuation, or even whitespace. Each token is mapped to a unique numerical ID, and that ID is then associated with a vector – an embedding – that captures meaning in a high-dimensional space. Words that are related in meaning tend to live closer together in this space. To the model, language becomes geometry.

Once tokenized, the real engine of modern LLMs kicks in: the transformer architecture.

Transformers introduced a powerful idea called attention. Instead of reading text strictly left-to-right and compressing it into a single memory, attention allows the model to look at all tokens at once and decide which ones matter most to each other. A word at the end of a paragraph can directly "pay attention" to a word at the beginning, without losing information along the way.

This ability to model relationships across an entire sequence is what gives LLMs their uncanny strengths:

- Summarizing long documents

- Translating between languages

- Extracting patterns from messy text

- Reasoning within a bounded context

- Producing fluent, human-like language

When you prompt an LLM, what you're really doing is conditioning this prediction engine. The prompt sets the context, the constraints, and the tone. From there, the model generates one token at a time, each informed by everything that came before it.

This is why prompt engineering matters. Small changes in wording can lead to large changes in output – not because the model is fragile, but because you're steering a probabilistic system operating in a vast space of possible continuations. Well-structured prompts act like rails, narrowing the range of reasonable next steps.

This extensibility is one of LLMs' greatest strengths. With the same underlying model, you can:

- Change tone (formal vs conversational)

- Change role (analyst, teacher, editor)

- Change task (summarize, critique, generate, rewrite)

All without retraining the model itself.

But there's an important limitation hiding in plain sight.

Despite how fluid and intelligent the outputs feel, an LLM is still fundamentally a single-step system. It takes an input, produces an output, and stops. It doesn't decide what to do next. It doesn't persist goals across time, and it doesn't act unless prompted again.

That design choice is not a flaw – it's a feature. It's what makes LLMs fast, flexible, and broadly useful; but it also defines the boundary of what they can do on their own.

And that boundary is exactly where agents begin.

IV. Where LLMs Hit a Wall

Despite their strengths, Large Language Models eventually run into a hard boundary—not because they stop being useful, but because the problems we ask them to solve quietly change shape.

As soon as a task requires more than a single, self-contained response, the limitations start to show. Real-world work rarely fits into one prompt. It involves multiple steps, external data, changing context, verification, and iteration. An LLM can reason about these steps, but it can't own them.

This is also where a familiar failure mode begins to appear: hallucination.

In AI, a hallucination is a response generated by a model that contains false or misleading information presented as fact. Importantly, these errors don't usually look like guesses. They often sound confident, coherent, and perfectly reasonable—until you check them.

Hallucinations aren't a sign that the model is "lying" or malfunctioning. They're a natural consequence of how LLMs work.

At a high level, there are a few common causes. Some hallucinations come from data-related issues: gaps, inconsistencies, or outdated information in the training data. Others are modeling-related: the model is optimized to produce plausible continuations of text, not to verify truth against the world. And some stem from interpretability limits—we still don't fully understand how or why certain internal representations lead the model down one path instead of another.

In isolation, these errors are manageable. A human can spot them, correct them, and move on. The problem is what happens when hallucinations appear mid-workflow.

Technically, this comes back to how LLMs are designed. They are stateless by default. Each response is generated in isolation, conditioned only on the context window you provide. Once the model produces an output, there is no inherent memory of what just happened, no notion of progress, and no built-in mechanism to ask, "Was that correct?" or "Should I revisit this step?"

This is why many AI-powered tools feel impressive in demos but brittle in practice. They explain what should be done, but they don't reliably do it. If an early assumption is wrong, the system doesn't notice. If an output is inconsistent, nothing reacts. The user ends up acting as the glue – copying outputs, fetching files, rerunning prompts, and correcting errors along the way.

As models have improved, this gap has become more obvious rather than less. The better LLMs get at language and reasoning, the clearer it becomes that intelligence alone isn't enough. What's missing is feedback over time – the ability to observe results, detect errors, and course-correct.

This realization has sparked a shift across the industry. Instead of asking, "How do we make the model smarter?" many teams are now asking a different question: How do we wrap these models in systems that can notice when something goes wrong – and do something about it?

That question is what's driving the move toward more persistent, goal-driven systems – systems that don't just generate responses, but can react to them. And that is the foundation for what comes next.

V. What an Agent Actually Is

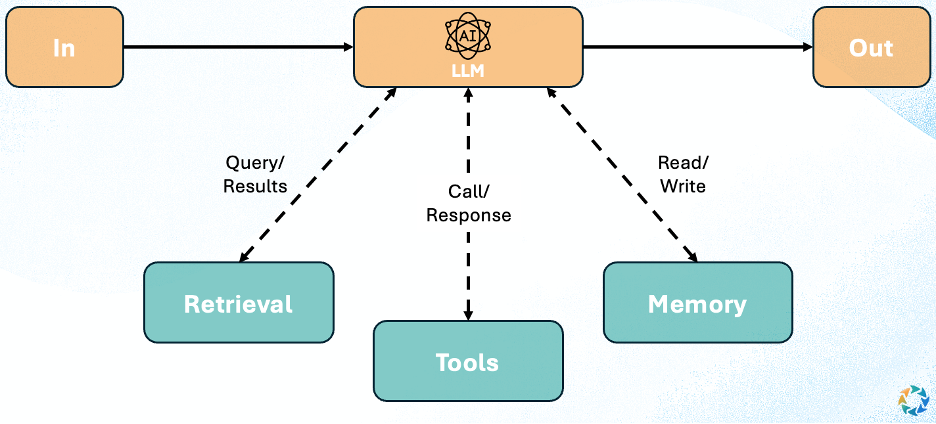

If an LLM is best understood as a powerful reasoning engine, then an agent is what happens when that engine is placed inside a system that can hold goals, make decisions, and act over time.

A helpful mental model is still J.A.R.V.I.S. from Iron Man. Not because J.A.R.V.I.S. is human-like, but because he embodies the right abstraction. He doesn't just answer questions. He monitors context, routes tasks, invokes tools, checks results, and keeps going until something is resolved. Importantly, Tony Stark doesn't micromanage each step – he delegates an objective.

That's the key shift agents introduce: from prompting for answers to delegating outcomes.

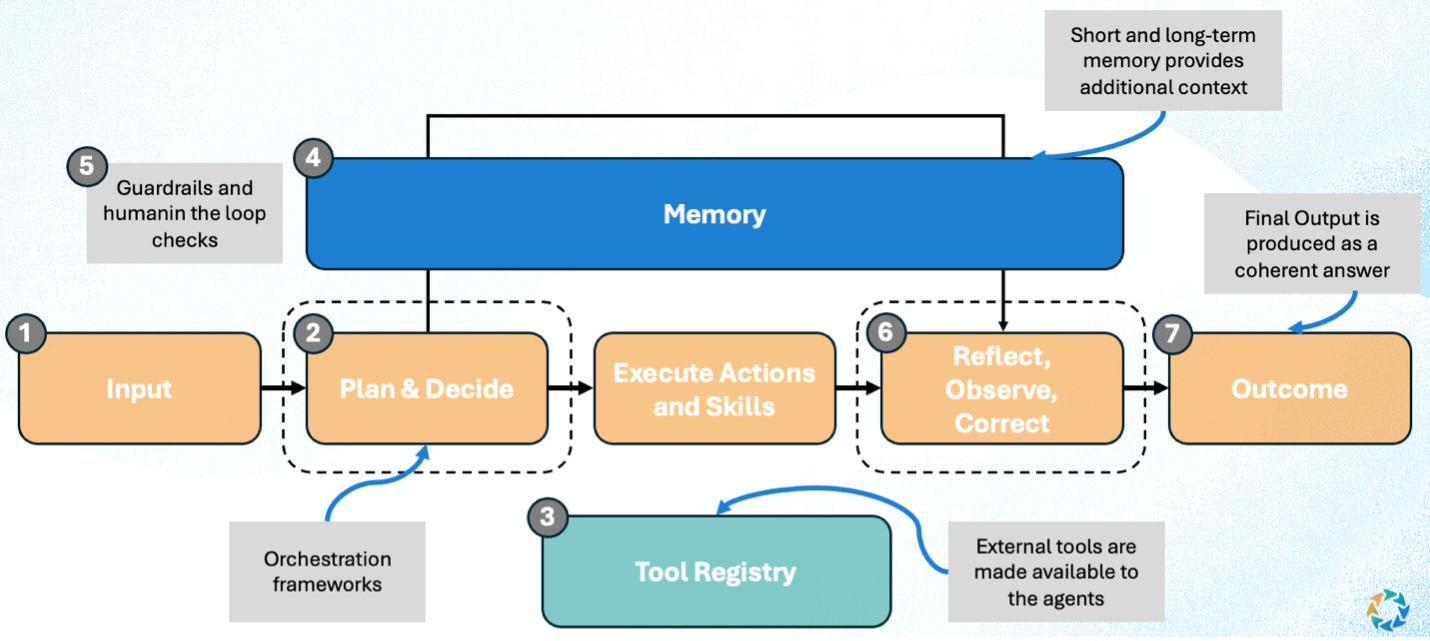

At a technical level, an agent is not a single model call. It's a cognitive loop built around an LLM. While implementations vary, most modern agents follow a similar structure:

- Interpret a goal

- Plan a sequence of steps

- Invoke tools or sub-agents

- Observe the results

- Update internal state

- Decide what to do next

This loop repeats until the goal is completed, fails, or is explicitly stopped. The LLM handles reasoning and language, but the system decides when to think, when to act, and when to reflect. This feedback loop is also what allows agents to catch and correct hallucinations – by observing their own outputs, checking them against tools or constraints, and adjusting course when something doesn't line up.

This distinction is subtle but profound. An LLM answers "What should I do?"

An agent answers "What should I do next?"

Agent Orchestration: How Complexity Is Managed

As tasks grow more complex, a single monolithic agent quickly becomes brittle. This is where agent orchestration patterns emerge – ways of coordinating multiple reasoning steps or specialized agents without losing control.

Three patterns show up repeatedly in serious systems.

Prompt chaining is the simplest. One step feed into the next: extract information, then analyze it, then format it. Each prompt is narrow and constrained, reducing ambiguity and error propagation. Instead of asking the model to do everything at once, the system decomposes the task.

Routing introduces decision-making. Based on the input or intermediate results, the system decides which path to take, or which agent should handle the task. For example, a question might be routed to a research flow, a document review flow, or a generation flow depending on intent.

Parallelization allows multiple reasoning processes to happen at the same time. An agent can search multiple sources simultaneously, compare interpretations, or run verification checks in parallel before synthesizing a final output. This mirrors how teams work – not sequentially, but concurrently.

These patterns are not theoretical. They're now appearing in production systems, including recent experiments like Claude Co-Work from Anthropic, which explicitly explores how AI agents can collaborate with humans across longer, more open-ended tasks.

The Cognitive Architecture of an Agent

What makes agents feel different from chatbots isn't personality – it's memory and control.

Agents typically maintain:

- Working memory (what's relevant right now)

- Task state (what's been done, what hasn't)

- Constraints and rules (what must or must not happen)

- Evaluation mechanisms (did this step succeed?)

This gives agents a primitive form of situational awareness. They don't just generate text; they track progress. They can revisit earlier steps, correct mistakes, or change strategy when new information appears.

In other words, agents introduce time into AI behavior.

What This Looks Like in Practice

At Caerus, this agentic approach shows up as distinct but coordinated agents – not as a single omniscient system.

- An Ask agent focuses on retrieving and reasoning over internal documents.

- A Research agent gathers and synthesizes external information.

- A Review agent evaluates outputs for clarity, accuracy, and structure.

- An Edit agent focuses on transforming insights into usable artifacts like slides or written narratives.

Each agent has a constrained role, its own prompts, and its own success criteria. Orchestration determines how they interact, when they run, and how their outputs feed into one another. The user isn't interacting with "one AI," but with a system that knows how to think about different kinds of work.

This is not about automation for its own sake. It's about reducing cognitive overhead. The more work involves coordination, context switching, and repetition, the more value agents unlock.

Why This Matters

The promise of agents isn't that they replace judgment or creativity. It's that they take over the monotonous, glue-like work that quietly consumes time and attention: searching, reformatting, cross-checking, re-explaining, and redoing.

As these systems mature, they have the potential to:

- Increase personal and economic productivity

- Enable individuals to operate at higher leverage

- Shorten feedback loops for innovation

- Free humans to focus on decisions rather than execution

LLMs made machines fluent.

Agents make them useful over time.

And once you experience software that doesn't just respond, but stays with the task, it becomes very hard to go back.

VI. Why Agents Unlock Real Workflows

The easiest way to understand why agents matter is to look at a workflow people actually do.

Take something simple on the surface: creating a company profile slide.

What looks like a single task is usually a chain of dependent steps. First, you need to understand what sections the original company profile includes – business overview, segments, geography, financials, strategy. That's an internal search problem. Then you need to find the same information for a different company, often pulling from external sources. That's research. Next, you have to create a new slide that matches the exact structure, formatting, and template of the original, but with new content. That's editing. Finally, someone has to check the output for mistakes, inconsistencies, and tone. That's review.

None of these steps are particularly hard. But together, they form a workflow.

An LLM can help with individual moments inside that flow. It can summarize a company. It can draft text. It can suggest structure. But it doesn't know what step comes next, whether the format matches, or whether the output is consistent with what came before. The human ends up coordinating everything.

An agentic system handles this differently.

Instead of treating each step as a new prompt, the system treats the entire sequence as a single objective. One agent focuses on understanding the structure of the original material. Another gathers comparable information for the new company. Another transforms that information into the same slide format. Another checks the result for errors and alignment. Orchestration determines the order, passes context between steps, and ensures nothing is dropped.

This is what it means for agents to unlock real workflows. The value isn't smarter steps – it's continuity. It's that the system maintains continuity across steps, coordinates different kinds of reasoning, and pushes the work to completion.

Once you experience this, the interaction model changes. You stop asking for individual outputs and start delegating outcomes. The AI isn't just responding – it's carrying the work forward.

That's the difference between tools that assist and systems that actually help you get things done.

VII. Conclusion: From Intelligence to Leverage

It's natural to ask what all of this means for people who actually do the work.

When new technology arrives, especially something as visible as AI, the first reaction is often anxiety: Will this replace me? Will my role still matter? History suggests a more nuanced outcome. Tools rarely replace professionals outright. They change where value is created.

Large Language Models were a massive first step. They gave software fluency, made interaction with machines feel natural, and dramatically lowered the cost of generating explanations, drafts, and ideas. But on their own, they mostly changed how fast we get answers – not how work gets done.

Agents are different.

Agents don't remove the need for judgment, context, or accountability. What they remove is friction. They take on the coordination work that quietly consumes time: searching, reformatting, cross-checking, carrying context from one step to the next. They make it possible for one person to reliably handle more complexity at once – without sacrificing accuracy.

For an individual professional, this means leverage. You can move faster, but more importantly, you can move cleaner. Fewer mistakes. Fewer dropped details. Less mental energy spent on glue work, and more on decisions that actually matter.

From a company's perspective, the implication compounds. When workflows are easier to complete end-to-end, output scales more smoothly. Teams can handle more work without proportional headcount growth. Revenue per employee rises not because people work harder, but because systems reduce waste.

This isn't about replacing professionals. It's about raising the ceiling of what one professional can do.

And this is where the distinction becomes clear. LLMs showed us what intelligence looks like when it's easy to access. Agents show us what happens when that intelligence can persist, coordinate, and finish things.

That's why agents aren't a passing trend. They're a structural shift. Once software can hold goals, manage workflows, and push work to completion, it becomes very hard to go back to systems that only answer questions and then disappear.

LLMs were the breakthrough.

Agents are the difference – and they are here to stay.

Not because they think for us – but because they let us think about the right things.

The shift will no longer feel like a foreign concept;

instead, it will feel like work is finally catching up to how it was always meant to be done.